Our Marconi Hong Kong office informed me that I was to transfer, bag and baggage, to a small river steamer named the Lung Shan for a period of eighteen months, so with a very heavy heart I said goodbye to all my good shipmates and took a rickshaw to the Kowloon Dry Dock where my new ship was lying under repair. It was mid-winter in Hong Kong and the nights particularly were very cold, so I viewed the coming days with some apprehension. A ship in dry-dock is never comfortable to live on, as the boilers are shut down and all steam heating is off. Any decent company would have provided me with hotel accommodation during the period of the dry-docking, but the Marconi Co. did not rank in this category. As usual they passed the buck to the shipping company which blandly refused to accept it. However, I found my quarters on board to be very comfortable and, as the ship was linked to the shore electrical supply I was provided with a very good radiator which solved most of my heating problems. My Chinese steward was very helpful and brought me all my meals on a tray to my cabin. Seeing that all the other officers were living ashore there would not have been much sense in my eating alone.

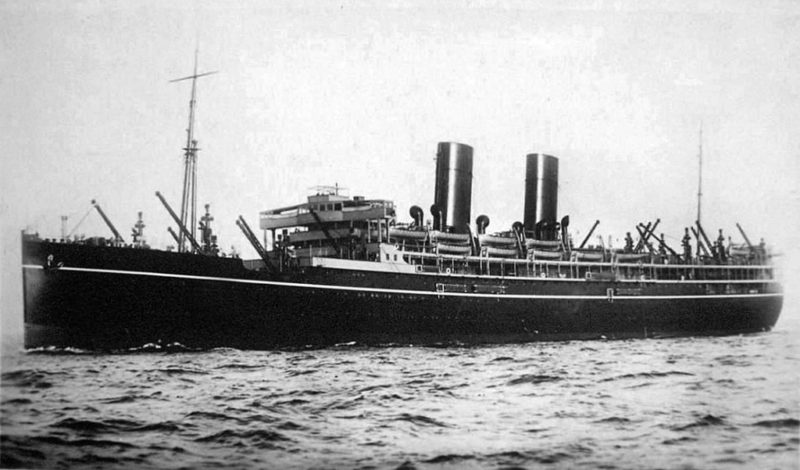

It has to be pointed out here that I was now a stranger in a strange land, and that few of the ruleson home based ships applied in Hong Kong. However, the Lung Shan was still a British ship sailing under the red ensign and registered in Hong Kong. The owners were the Hong Kong, Canton, and Macao Steamboat Co. (herein-after called The Steamboat Co.) and their business was running a ferry service between Hong Kong and the two other ports of Canton and Macao, the former in China and the latter a Portuguese settlement, both on the delta of the Pearl River. The Lung Shan was imposingly big for a ferryboat with passenger decks right from bow to stern and two tall funnels. I found that she had a passenger certificate for about 3000 souls, carried a crew of about 300, with a New Zealand captain, two British deck officers, and two certificated engineers, the Chief being a Chinese and the Second a Scot. Some of the names I have since forgotten, but the Captain was named Thomson, the Chief Officer Carter, the Second Officer, an expatriate Australian, named Town, while the Second Engineer was old Jock Spence a Glasgow Scot who had lived most of his engineering life on the China coast.

The Lung Shan had been built some years earlier in the shipbuilding yard which contained the dry dock where she was now undergoing overhaul. Reputed to be quite fast, about twenty knots, she had twin out-turning screws, of which more later. The other officers mostly had their homes in Hong Kong so never slept on board while the vessel was in Hong Kong. The only exception was the 2nd officer who turned out to be one of those footloose characters to be found all over the Far East. He had been in very many shipping companies in his time from which he had mostly been sacked on account of having an outsized drink problem. He was a good but dangerous shipmate and I still remember him in a very kindly way. In fact he was the first man to greet me to my new ship when he called on me the first morning while I was still in my bunk. He lived in the cabin next door and was carrying a bottle of Gordon’s Gin with which he proposed to help me set myself up for the day. In spite of only a moderate hang-over from the evening before, I declined the drink, and watched with fascination while he downed two burra pegs in quick succession. I claim no special virtue for the fact that no matter how bad I felt the next day I could never face the proverbial ‘pick-me-up’. The peculiarity has probably saved or lengthened my life over the years. I could also enjoy a hearty breakfast despite a major hangover, and never joined the ranks of the poor sods who breakfasted on an aspirin and a cigarette.

Until now my approach to life with the Company had been pretty happy-go-lucky. I had not cared a great deal where I went or what kind of ship I got until the protest of 1929 which had landed me on my first passenger ship for ten years, the beautiful Arcadian. But here was something else! During my ten years in tramps I would have been most happy to serve on the Indian Coast, the China Coast, the South American Coast, or on any of the beautiful ships running regularly between Canada, Newfoundland, Bermuda and the marvellous West Indies ports in the fabled Caribbean Sea. In some strange, accident always I had fallen between two stools, missing out on the splendid trans-Atlantic passenger service on one side, and equally missing out on the comfortable small passenger ships engaged in Foreign Service. Now, here I was a totally unwilling victim of Foreign Service, landed on a beautiful little passenger ship I did not want but which I would have given my boots for five years earlier. I now knew the meaning of that age-old cliché ‘the irony of fate’. However, married or not, I was a pretty resilient character in those days, so, after lodging a strong protest with Mr Cobham, the Hong Kong depot manager, together with a plea for early repatriation, I had to make the best of it.

And there was plenty about Hong Kong to enjoy. I feel privileged that I was granted the experience of seeing Hong Kong while it was still relatively untouched. In 1930, the population was less than one million, and the New Territory of Kowloon on the mainland (where the dry-dock was situated), was still sparsely peopled by a Chinese community surrounding the European section centred on Nathan Road and the new luxury hotel known as the Peninsular, which dominated the Kowloon dock area and the Star Ferry landing place. I never got tired of contemplating the view of Hong Kong Island as seen from Kowloon. The small city of Victoria nestling around the base of high Victoria Peak and spread-eagling itself in a scattered and inverted ‘V’ shape right up to the apex where none but the wealthiest of merchant princes lived. Seen at night, the whole scene was like some kind of gigantic fairyland. The harbour itself beggared description for its variety. Warships at anchor mingled with huge sailing junks and the smaller sampans, while merchant ships of every sort and size jostled for place at the many buoys, or more fortunately at one of the few available berths alongside at Kowloon. The atmosphere of a tremendously alive and palpitating business community was almost tangible. Strangely, it has to be said here that, in 1930, Hong Kong was also feeling the bite of the depression that was to blight the whole world for another five or six years. The waterfront on the Hong Kong side of the harbour was more devoted to small craft and centred on the landing stage of the Star Ferry jutting out from the main dock road and abreast of Pedder Street in the midst of Hong Kong’s bustling business section. Pedder Street was indeed the site of the Marconi Office where Mr. Cobham held sway, ably backed by his redoubtable Chinese Staff Clerk Mr. P. N. Ho. Old Ho and I became very good friends He was small, dapper, and good looking, and, later I was to find that he was married with a considerable family of small ‘Hos’. He also spoke beautiful English, which he also wrote with remarkable precision. Pedder Street also ran up the hill towards the Peak, crossing on its way the lateral streets of Des Voues Road and Queens Road, the latter being the main shopping street of the European section of the city. Not that I was ever quite sure where that section started or finished, because, in a curious way H.K. always seemed to me to be the perfectly integrated Anglo/Chinese town. In 1930 it also had a strangely provincial character in some ways, which showed itself in the petty gossip of the Europeans. One had to be careful of one’s reputation here, because any blemishes or misdemeanours soon got around. Class distinction, while in evidence, was not as pronounced as I later in life found it to be in Bombay or Calcutta, but there was still a pecking order with the Royal Navy headquarters at Stonecutters Island in predominance. Then came the Army, followed by the business section which I think included the Merchant Navy and finally the Customs and Excise closely followed by the Hong Kong Police in the bottom bracket. But by-and-large there was little of protocol observable in Hong Kong and I grew to be very attached to its free and easy ways and lack of snobbery.

Shipping in Hong Kong was big business in anybody’s language and at the head of this monolith were the two great British companies of Jardine Matheson and Butterfield and Swire, of which the latter the Steamboat Co. to which I was now attached was tenuously connected. The Hong Kong, Canton, & Macao Steamboat Co. had six ferry boats of which the Lung Shan, Tai Shan, Kin Shan and Fat Shan ran to Canton only, while the Sui An and Sui Tai ran only to Macao. One of the principal shareholders and also a director was the local Sir Robert Ho Tung, a very wealthy businessman with a palatial home atop of the Peak. As he was also a director of Butterfield & Swire it will be seen how the companies linked up laterally, and it is of interest that the Fat Shan was believed to be wholly owned by Butterfield’s. It is certain that her officers were not interchangeable with those on the remaining three ships on the Canton run. Then, there were many smaller companies, some of them wholly Chinese owned, usually having a good sprinkling of British officers. In close competition with our own four Canton ferries were the two fine ships of a company whose name I have forgotten but which were named the Sai On and Tung On. Comparatively of similar size, they berthed at the other side of the Steamboat Jetty and sailed an hour earlier for Canton. When we took up our run on the Lung Shan, our departure time was 10pm arriving at Canton 6am the following morning. I suppose there was a state of friendly rivalry between the two companies, but it did not show in any fraternising between the officers. I once watched the Chief Officer of the Tung On pacing the boards of the wharf between our two ships in the company of his very beautiful wife, and wondering why inter-ship salutations were not in evidence. The hard fact became evident to me with time that ‘China Coasters’ were not as other folks. They were a race apart, and to some, little better than pariahs. Officers sacked from the British India, the Blue Funnel, Andrew Weirs, or even Jardine Matheson, could usually get jobs in the Steamboat Company to begin with. It represented the best of the Hong Kong based concerns. It was a bit like going down a ladder because, following dismissal from the Steamboat Co, the company of the Sai On and Tung On was the next most prestigious on the way down. Thereafter there was a list of small totally Chinese owned passenger ship companies all trading to all ports between Shanghai and Singapore. They all needed the expertise of British officers and those throw-outs from the top were always welcome so long as they could produce a Master’s ticket. One quite notorious concern which ran a passenger ferry to Canton, called the ‘Tin Yat’, was reputed to engage captains only if they had been captain before and could prove it. The reasons for this crop of available Board of Trade certificates in Hong Kong were not far to seek. Many of the cast-offs were alcoholics while others might have had temporary certificate suspensions. Some had left the great companies following legitimate disputes or quarrels with their captains or superintendents. After all, it was never at any time in the first half of this century very difficult to get fired from the British Merchant Service for disciplinary reasons. I doubt if there was ever any profession which possessed in its ranks a greater percentage of half-educated, arrogant, self-opinionated, sadistic slobs posing as officers. So, I found myself on the sweet little Lung Shan, shipmates with as pleasant a bunch of drop-outs or Hong Kong beachcombers as I could have wished for. Captain Thomson, who had his wife and family in Hong Kong, I saw very little of as he kept very much to himself and never dined in the Officers’ Mess. Carter, the Chief Officer was a man already past middle age who had been in the Blue Funnel Line. Very Oxford accented, particularly when he’d had a few, and we got on famously. I was just off a big P&O boat so that put me high in his estimation, for he was also a terrible snob but in the nicest way.

Unmooring and getting under weigh was a very well executed routine in which the Captain manoeuvred the ship’s engines first by means of a telegraph situated at the outer rail amidships. When clear of the quay he shifted to the bridge. In all this he was assisted by two permanently carried Chinese pilots, one of whom assisted the second mate aft while the other remained on the bridge. The Lung Shan handled beautifully and there is a nice picture of her in my album steaming away from the Steamboat berth at Hong Kong towards Cap Sing Moon Pass and Canton. Of the four Canton ships, the Lung Shan and the Tai Shan were sisters, although by no means alike in looks, apart from the fact that both had two funnels. The Tai Shan had twin in-turning screws fitted when she was built fairly recently at Tai Koo dockyard on Hong Kong Island. The Lung Shan, somewhat older, had been built at Kowloon on the mainland and had out-turning screws. Those expressions mean exactly what they say and so the latter’s propellers turned away from each other when going ahead. This turned out to have been a mistake, because, at one point in the river passage up to Canton, the propeller wash was so heavy that the ship had to be slowed down for some miles to avoid serious flooding of the low lying paddy fields on either side. It had been known for Chinese guerrilla snipers to fire on ships guilty of such behaviour. But, as this was an era of great instability in China, that danger was ever present with or without the propeller wash.

This brings me to the very real danger of piracy that existed on the China coast generally at that time. The Lung Shan was well equipped to counter any such eventuality and we were all armed with quite business like looking revolvers. My own, which I kept ready in the drawer of the radio room table, was a Colt 45 complete with a box of spare ammunition. The bridge area of the ship which was in reality the forward quarter or so of the uppermost full length deck was fenced in at the after end by a closely knit palisade of steel bars extending vertically to the permanent fore-and-aft awning. This was in fact known as the grille and it was also extended well beyond the ship’s rail on both port and starboard sides by huge parabolic rigid ‘leaves’, around the periphery of which were a series of closely spaced and lethal looking spikes. The grille had only one door, situated on the port side just abaft the doorway into the radio room and berth. This door was kept locked while the vessel was at sea and both sides were guarded by a stalwart Sikh policeman in uniform and complete with Lee Enfield rifle plus bayonet. While at sea, none of us (the officers living inside this barrier) were allowed to pass through the grille doorway on any pretext whatsoever.

My quarters on the Lung Shan were, as I have indicated, at the after end of the of the bridge complex and immediately ahead of the anti-piracy grille, with one door on the port side. There were two rooms, the outer of which was the wireless room and the inner my living room and sleeping berth. The latter was beautifully secluded, and was fitted out in a most comfortable fashion with a narrow fore and aft bed, a full length thwart ship settee, a wash-hand basin with running hot and cold water, a writing desk and, last but not least, a huge basket-work armchair. The Wireless room was of similar size and also had the same washing facilities on its after side.

The radio equipment was the most basic possible and something I eyed with considerable disappointment. The main transmitter was an old-fashioned quarter Kw cabinet set which really was little improvement on the morse lamp, whilst the receiver was the now well established RM4B of which I have already spoken about at length. I was to find very soon just how ineffective this layout was because it only took one voyage to Canton and back to disclose that the Pearl River delta area was almost totally screened from the outside world in a radio sense by the high land of the islands. I do not ever remember being so ashamed of my log book as I was on that run between Hong Kong and Canton. I used to send a TR to the great Hong Kong naval/commercial station at Stonecutters Island, call letters VPS, soon after leaving the wharf in H.K., and that was almost the last I heard of that station after passing through Cap Sing Moon Pass. The many ships in the China Sea outside which are usually much in evidence chattering away in morse on and around 500 Kcs. seemed almost to have disappeared, and nothing seemed to be left but the continual drone in the background of an unidentified station, call sign XOW, which I later found to be Foochow Radio. (He had not yet been noted in any of the International Lists). XOW appeared to be the main link in China’s communication system. He was on the air 100% of the time sending interminably to other unknown stations in some strange inexplicable code. So, more than half of my log entries were merely a brief ‘xow working’. From what I now remember, he wasn’t even on 500 Kcs., (our standard listening frequency) but actually on a much longer wavelength which was very broadly tuned or which had such a strong 500 Kcs. harmonic that his signals came through also on 600 metres. It was a bit of a joke among the small coterie of Radio Officers on this trade, namely that it would have been possible for any of us to sleep all the way to Canton because the log entries were always the same for any voyage.

I refer of course to my colleagues, J.M. (Fat) Powell on the Tai Shan and Meurig Evans on the Kin Shan, both excellent chaps in every way. Powell in particular was most popular. Big, portly, eternally good-natured, cheerful, and quite imperturbable. He was a bachelor with about the same seniority as myself, and although he used to throw splendid parties in his cabin in the most open-handed and hospitable way, he was reputed to be careful with his money. Evans told me that ‘Fat’ had a bank balance of £3000 at that time which must have been some kind of record in the notably impecunious fraternity of Radio Officers. Evans of the Kin Shan was quite different but also a most likeable chap. A Welshman from the wilds of Cardigan, he was most open handed and always good company at our many gatherings on board any of the three ships when they happened to be in port together. If he had a fault, it was his liking for the ladies, and he always seemed to have a Chinese girl at his disposal. Even as late as 1930, the old China Coast tradition of ‘sew-sew’ girls had not died out. It was permitted by certain coast shipping companies that unattached ships officers could carry on board their Chinese mistresses ostensibly for the purpose of looking after the men’s wardrobe. They did his mending and sewing for him. The arrangement was so eminently practical and worked so very well that it would almost seem that those enlightened shipowners were ahead of their time. That the custom was frowned on by other companies is certain, and I fancy that one of those was the great house of Jardine Matheson who owned many ships in Hong Kong, and who were also deeply involved in banking and trade generally on the China coast. A purely Scottish concern in origin, and no doubt therefore, touched by the dead hand of the all-seeing ‘Kirk’. I do not think that any of those girls was carried in the Steamboat Company ships, but then, there wasn’t much need to because the ships were only at sea for eight hours out of the twenty-four, and every weekend was spent in either Hong Kong or Canton. Many ladies of different colour came aboard in Hong Kong, including the wife of Mr Carter the Chief Officer, who was quite a character in her own right. She was a Russian from Byelo-Russia and had seen much of life in her time, having arrived in Hong Kong in the twenties from far-off Europe via Moscow, Ekaterinburg, Omsk, Tomsk, Tobolsk, Irkutzk, Vladivostok, Shanghai, Swatow and Amoy. This she used to declaim while in her cups, always ending with the loud assertion that ‘I not Russian, I am Cossack’! She was great fun in comparison to her elderly husband who adored her no matter what she had been through. Her age would always have been difficult to assess, but she was handsome, very friendly and extravagantly kind. I think we all loved her to some extent and she had pet names for everybody. I was Lukoshka while Fat Powell was Pompushka. She spent all her available time on board while the ship was in Hong Kong and occasionally did a trip to Canton. Altogether, I enjoyed the best of shipmates on the Lung Shan during those two long years I was to spend onboard her.

Neil Semple retired from service with Marconi in the late nineteen sixties, after a virtual half century in their employment. His memoirs are a record of times both near yet far away, for the technology that made such men indispensable has developed beyond all recognition, and rendered them all but redundant forever.

It has been a pleasure to have transcribed over four hundred pages of his seagoing memories, and to have distilled only a few of them here. Grateful thanks are due to his daughter Patricia Semple, for allowing me the privilege to do so.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item