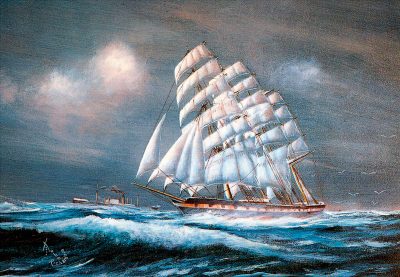

Beechbank

Russell & Co of Port Glasgow launched the Beechbank on 3rd February 1892 with yard number 289. She was a four masted barque measuring 2,288 grt with the dimensions of 277.5 x 42 x 24.2 feet. After tramping around the world when mainly carrying coal from either South Wales or Newcastle, NSW, the Beechbank was sold in 1913 to E. Monson of Tvedestrand, Norway. Early in 1916 during WW1 when she was on passage from Iquiqui towards Copenhagen with nitrates, she was firstly intercepted by a British armed merchant cruiser when sailing north of Scotland, and ordered into Kirkwall, Shetlands for examination. On the same day she was hit by a terrific storm and lost many of her sails, spars and became badly damaged. Then another British armed merchant cruiser HMS Ebro came to her assistance and escorted her into Kirkwall. Once seaworthy she went to London for a major refit. During her repairs later in the year of 1916, she changed hands to O. Stray of Kristiansand who renamed her Stoveren. He kept her until 1922 when she went to Norsk Rutefart of Norway. The four masted barque was scrapped in 1924.

However, during her career in Andrew Weir’s fleet, on 5th January 1907 an apprentice named Victor Harbord joined the Beechbank at Port Talbot. He was making his first trip to sea. His first ship’s destination was to the Peruvian port of Iquiqui, (pronounced aye kee kee) with a cargo of coal. Victor came from a family of sailors of which his father Captain Richard Harbord OBE, and his three elder brothers, were all seasoned seamen who’d been brought up in sail. Young Victor had wanted to pursue a life in steamships, but his father told him that if he wanted to get any money from him for his indentures, then he had to start off in sail. Therefore, it was due to the wishes of Victor’s father that the young man signed his four year indentures with the Andrew Weir Shipping & Trading Co. Apprentice Harbord remembers only too well the day he joined his first ship in Port Talbot. It was on a cold and icy day of January 1907. Mr Webb the mate welcomed him on board at the top of the gangway, took him to the saloon and introduced him to Captain John R. Bremner, then put him to work breaking the ice off a load of dunnage on the quayside, and then stow the planks on board. Also in his memory was his first rounding of Cape Horn, and what he’d heard about that notorious stretch of water turned out to be true, indeed the Beechbank took a 15 day pasting in sailing around The Horn, and Victor recorded some notes on the ordeal.

22nd March 1907 – Ran into very bad weather, ship labouring with heavy seas coming aboard.

26th March 1907 – Latitude 60°25′ South Longitude 72°48′ West. Still beating around Cape Horn.

31st March 1907 – Still beating to windward.

2nd April 1907 – Shocking weather. The ship is labouring heavily. Mate’s and apprentice’s rooms flooded out. The ship is taking a lot of heavy water on board. Two men are lashed to the wheel.

6th April 1907 – Rounded Cape Horn, Very cold weather, heavy seas and snow squalls.

Victor and his six other apprentice shipmates had lots to learn. As well as climbing the rigging, they had to set and furl canvas as well as stitching it, and ensure that every rope was always in its proper place. There was also boxing the compass, learning how to steer with quarter points, and many other sailorising jobs. Then of course there was the holystoning the wooden decks, a task which was otherwise known as ‘bible practice’.

On arrival at Iquiqui the apprentices had to supervise the coal discharge, and then ensure that the hold was thoroughly cleaned before loading at Pisagua. After loading a cargo of salt petre the Beechbank’s next destination was Cape Town. From there the ship went to Adelaide in ballast where on arrival she anchored awaiting orders. On Sunday 24th December 1908 the ship berthed at Port Augusta, and then on Christmas day the ship was ‘dressed’ and thrown open to the public. Captain Bremner invited Reverend Wilkinson and his friends on board and they returned the compliment by taking the seven apprentices on a picnic. Beechbank left Port Augusta on 15th March 1909 and made a 109 day passage to Belfast. Victor went home on leave and rejoined at Cardiff where his ship was loading coke for Albany, New York.

At the end of the nineteenth century the victuals on ships would never come up to today’s standards. On the Beechbank there was a daily ration of eight ‘Liverpool Pantiles’. These rock hard biscuits were normally ages old, full of weevils and had to be thoroughly soaked before being eaten. Salt fish and salt pork as well as South African dried stringy meat named biltong were other additions to our cheap meal allowances. Another one was ‘Harriet Lane’ a tinned meat product that’s regarded as being a bit of a luxury. Apparently, the name for this tinned meat got its name from a London meat canning factory in the mid nineteenth century. It so happened, that one of the women workers in the factory named Harriet Lane, who regularly prepared the stewed meat for canning, suddenly disappeared! Because she’d recently had an altercation with her employer, he was accused of chopping the woman up and putting her into the huge stew pot to hide the evidence. Despite police intervention nothing was ever proved, but the name of ‘Harriet Lane’ stuck. Furthermore, that woman’s name was given to all the stewed meat products that came from that meat canning factory. Moreover, because the Londoners would no longer eat the products of that factory it was sold off cheaply. Therefore, it came as no surprise when ship owners revelled in the cheap food and bought all that was left and used it for crew meals. As a result of it all, and even many years after the meat canning factory had gone out of business, tinned meat was forever after called ‘Harriet Lane’ on ships of sail. A cup of tea on a ship never had any milk or sugar in it, and was similar to the porridge that was called ‘goolash’. A week after a ship had sailed any fresh meat quickly disappeared from the menu, spuds and onions lasted longer but like the drinking water they were kept locked up. To prevent scurvy lime juice was part of the rations, as was a daily issue of four quarts of water, half of which had to be handed over to the galley.

Victor’s recollections of his four years apprenticeship on the Beechbank are a vivid memory as are the two weeks spent in the ‘roaring forties’ battling against the strong winds and high seas. On one occasion he was sent aloft in the dark to secure a loose sail. The seas were so heavy and the ship being thrown about so much, that after he had made the sail fast he was unable to get down again and spent several hours clinging to the rigging. Such was the life that Victor led for the whole of his apprenticeship. When he finally left the Beechbank after serving his four years apprenticeship he received a massive pay-off of £28. Victor Harbord never returned to sail but continued his life at sea in steamships and worked his way up to the rank of Master Mariner. He later became a Humber Pilot and later in the Thames and Clyde, eventually completing 28 years as a pilot. During WW2 he was selected by the Admiralty to be an examining officer.

Cedarbank

This four-masted steel barque of 2,825 grt was launched in June 1892. She was built by Mackie & Thompson of Glasgow to the order of Andrew Weir & Co. Her other dimensions were 326 x 43 x 24.5 feet. Her sister ship was the Olivebank, and those two large vessels were the pride of the fleet. Both of those ships had steel wheel houses on the poop deck to protect the helmsman if the ship got pooped. They also had a donkey engine for hauling in the anchor as well as for a fire hose line. But none of Andrew Weir’s ships ever had the modern style Liverpool House amidships, a point from where the ship could be steered with chain and rod gear, and also where the crew could be accommodated. The Cedarbank’s first master was Captain Andrew D. Moody, his crew had all signed on at Glasgow, but his ship almost came to a premature end when she was on her maiden voyage after her coal caught fire. After leaving Sydney while still on her maiden voyage, the ship was towed 60 miles up the coast to Newcastle where she loaded 4,800 ton cargo of coal for San Francisco. But when she was halfway across the Pacific Ocean, the deck plates were found to be unnaturally hot, and that spelled ‘fire’.

Coal itself comes in different forms with the best steam coal in the world ‘arguably’ coming from South Wales in the UK. But it appears that in 1892, a seam of inferior slate coal was mined at Newcastle, NSW and designated for export. Slate coal has always been well known for its instability as it splutters and spits out gas as it burns. Indeed, those of us who have sat before a coal fire will know only too well, and especially when burning cheap slate coal, that a fire guard has to be placed before an open fire in case the coal spits out dangerous sparks.

Cedarbank left Newcastle, NSW on 5th March 1893 bound for San Francisco with its 4,800 tons of coal. All went well for the first five days, but during 12th-15th March the ship was hit by a Pacific Ocean hurricane. Damage to her spars, rigging and loss of sails obliged Captain Moody to turn around and head for Sydney. The fully laden ship arrived there on 21st March, where after five weeks of repairs she once again sailed for San Francisco on 28th April.

A coal fire in the hold of a ship, which is better known as internal combustion, can often take many weeks to materialise and reveal itself. Indeed, when the Cedarbank left Sydney her coal may have already been alight. But after having been at sea for 53 days when the ship was in a position just north of Midway Island, those dreaded wisps of smoke were seen to be seeping out from beneath number two hatch tarpaulins, while at the same time the decks were becoming increasingly hot! If the Beechbank had been built of wood she’d have long since burned, and wouldn’t have even got half way. So much for steel and iron versus the out dated wooden collier ships!

On realising the cargo was on fire Captain Moody had a tough decision to make. Should he head for the nearest landfall, where any kind of assistance would be next to zero, or should he continue his passage in the hope of making San Francisco? After a consultation with the mate he decided to push on for ‘Frisco. At first light on the following morning, number two hatch was stripped and the crowd began discharging as much of the smouldering coal as they could, while at the same time every stitch of canvas was set. The sailors in the smoke and gas filled hold worked intermittently, but after ditching a few hundred tons, they then realised that the fire was slowly gaining and the hatch was battened down again. Two boats were fully provisioned and towed astern for a few days. But the weather came up and they had to be brought back onboard again. It was a torrid five weeks from when the fire was discovered, to when the Cedarbank finally arrived at San Francisco on 26th July after an 89 day passage. During that time water had been pumped onto the heated coal and the pumps were swung day and night to take the water from the bilges. Clouds of steam and smoke had emitted from the hold and many hatch boards were blown off. Taking a tow from the unsuspecting tugs the ship was first beached, and then the hold was flooded by the fire fighting tugs, after two to three days when the fire had been extinguished the water was pumped out and the ship towed away to discharge her cargo. Needless to say most of the cargo was saved, but the inside the hold was a mass of twisted beams with the hold ceiling badly burned.

After being repaired for the second time in five months, the Cedarbank took a cargo of grain back to the UK. From there she went out to Australia again and continued tramping with coal and grain until Mr Weir began disposing of his sailing ship fleet. Cedarbank was sold in January 1914 to E. Monson of Tvedestrand, Norway, with Captain Abrahamsen taking command. Two years later in 1916 with WW1 at its peak she was sold to Rederiselskabet A/S Cedarbank of Farsund, Norway. But that company didn’t keep her long, because while she was homeward bound on her first voyage for her new owners, she left Savannah with a cargo of oil cakes via Halifax Nova Scotia on 9th May 1917, on passage towards Aarhus, Denmark. The year of 1917 was the worst of all the war years for ships being sunk by submarines, the war at sea had reached its peak and ships of sail were easy prey for submarines. In the North Sea on 14th June 1917 the submarine U-100 had the Cedarbank in her sights. The unarmed sailing ship had no radio and was therefore no danger at all to the U boat. But to Commander Dagenhart von Loe it was no excuse. His orders from his superiors were to sink enemy ships without warning, not even giving their crews a chance to take to the boats. The philosophy of the German High Command was that rescued men and survivors could man other ships. He therefore torpedoed the helpless ship leaving 26 sailors to their deaths. The only trace that was ever found of the one time pride of Andrew Weir’s fleet was a few days later on 17th June 1917, when one of the Cedarbank’s empty lifeboats was found drifting off Flo Sunnmore, Norway.

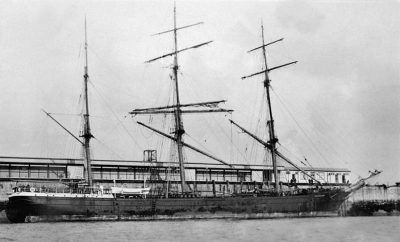

Olivebank

The Olivebank was launched on 21st September 1892, three months after her sister ship Cedarbank. Her first master was Captain J. N. Petrie, but any information on the ship for the next seven years is presently obscure. This may be due to the fact that during those years when steam ships were rapidly taking the business from sail, it was quite normal to see vast numbers of sailing ships being laid up for long periods of time all around the world. However, it was in 1899 that the Olivebank left the UK for Chile with coal, and then went onto Australia in ballast. In the following year she made a fast passage from Melbourne to Falmouth in 87 days. The next news on the ship is in February 1909 when she arrived at Santa Rosalia, California with coal from South Wales.

Under the command of Captain Carse she later sailed in ballast to Newcastle, NSW and loaded 4,800 tons of coal. Her destination was back to Santa Rosalia, but after she’d arrived there, and while she was lying at anchor in the shallows, it was then discovered that her cargo of coal was on fire. The fire fighting tugs came alongside and after the best part of two days put the fire out, but there had been so much water pumped into her hold that the Olivebank ended up sitting on the bottom with little or no freeboard showing. After being refloated and her coal discharged she went for repairs.

Captain Petrie was relieved by Captain David George. But after those repairs had been completed four months later, she was thrown against the Santa Rosalia sea wall in a hurricane on 29th June 1911. In that accident one sailor was killed and the rudder was badly damaged, and that necessitated a further delay for repairs. Despite being insured and with commanding a good freight rate on its 4,800 ton cargo, it was a voyage in which the unfortunate ship made a loss for her owner.

On completion of the voyage the Olivebank was sold in August 1913 to E. Monson. The next news of the ship came when she went to Rederi/As Heinschien of the same port. Two years later she went to The Kristiansand Shipping Co. They renamed her Caledonia and also kept her for two years before selling her to J. Lorentzen of the same port. In 1924 the ship was once again sold after a two year period of ownership. This time she went to Gustav Erikson of Mariehamn, Finland. Captain Erikson had always been a firm believer that a ship’s name should never be changed, so the first thing he did was to give Olivebank her original name back. With no cargoes offering, the Olivebank sailed on spec from her new Mariehamn port of registration to Cardiff looking for a coal cargo. But because there was nothing available anywhere in South Wales, she once again sailed on spec, this time in 93 days to Port Lincoln in ballast under Captain Troberg.

After receiving orders to load at Port Victoria, Olivebank loaded wheat and then had a slow 147 day passage back to Falmouth for orders. So slow had the passage been, that Captain Troberg wasn’t a bit surprised to learn on his arrival that he’d been posted ‘posted missing’ by Lloyds. On discharging no outward cargoes were available, so once again Olivebank went out to Port Lincoln ‘light ship’ looking for a cargo, and once again she took 93 days to get there. With nothing available her new master Captain Granith received orders that a cargo of guano was awaiting him in the Seychelles. On 24th April 1926 he sailed his ship from Melbourne for Mahe, arriving there on 27th June. The cargo was loaded and he sailed for Dunedin on 16th August 1926 arriving there on 13th November.

From then on the Olivebank joined in on the grain races with a large number of other sailing vessels. Those grain races had in fact begun in 1921 and ended in 1939. It was an annual event and the winners in order of year from 1921 being, Marlborough Hill, Milverton, Beatrice, Grief, Beatrice, L’Avenir, Herzogin Cecilie, Herzogin Cecilie, Archibald Russell, Pommern, Herzogin Cecilie, Parma, Parma, Parma, Passat, Priwall, Herzogin Cecilie, Pommern, Passat, Passat, Moshulu, Viking, Passat.

The Olivebank took part in 13 of those grain races, and although she had the capabilities to win she never won any of them. However, Gustav Erikson’s ships won 18 of the 23 races which ended at the outbreak of WW2.

During those Grain Races the Olivebank was under the command of the following:

1929-1931 Captain K. F. Lindgren, from 1931-1933 Captain J. M. Mattson, from 1933-1937 Captain A. L. Lindvall, and from 1937- 1939 Captain C. Granith

After having discharged her Australian wheat at Barry Docks, it was on 29th August 1939, which was six days before the declaration of WW2 that Olivebank sailed from Barry to her home port of Mariehamn. However, on her arrival at the South Wales coaling port, a number of apprentices paid off and took a ferry back to Finland. They had done their time and wanted to sit for their tickets. As a result the short handed Olivebank left for Mariehamn with a crew of 21. With Finland being a neutral country a large Finnish flag was painted on each of her ship’s sides as well as the hatch tarpaulins. Just to be on the safe side her boats were kept swung out. When the ship was off Dover a British destroyer approached with the information that the Royal Navy had not sown any minefields on Olivebank’s proposed route, but strongly suspected that the Germans had. Captain Granith therefore posted two look-outs day and night, one the foc’sle head and the other up aloft. Ten days after leaving Barry and when the ship was in the North Sea, Olivebank ran into a minefield near Bovbjerg off the Danish coast. But because the water was comparatively calm and shallow, the anchored mines which should have been about ten feet below the water were visible and floating on top. On the lookout’s three bell ring, and his verbal report of “Mine Right Ahead”, Captain Granith ordered the wheel hard over. The Olivebank missed that mine but as she swung around she hit another that was submerged in deeper water. The result of the explosion was catastrophic. Masts, yards and other spars came crashing down, the ship’s empty hold filled rapidly and the ship quickly developed a port list. So quickly did everything happen that those onboard could do nothing except jump over the side and swim for their lives. Nobody on board was wearing a life jacket and those in the water could only grasp at anything that was buoyant and hold on to it. The 47 year old Olivebank quickly sank.

Fortunately for some of the crew, the ship had sunk in shallow water with a heavy list to port, with the fore upper t’gallant yard sticking up out of the water and pointing skywards. Seven of the crew managed to reach it and lash themselves onto it. But they had to wait there all night and most of the next day in the cold waters of the North Sea before rescue arrived. Eventually a trawler named Talona, whose skipper was Captain Soren Hansen approached the sunken wreck. He took the seven survivors off and landed them at Esbjerg. Fourteen men had perished in the sinking with Captain Carl Granith being one of them.

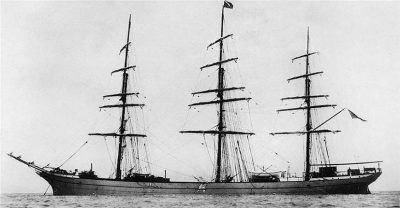

Trafalgar

In 1893 the company brought in the four masted iron ship Trafalgar which had been built in 1877. Her builder was Charles Connell of Glasgow, yard number 106, while the first owners were the Australian brothers W. & A. Brown of Sydney. Captain Brown was the ship’s first commander. The Glasgow registered Trafalgar was 1,765 grt with dimensions of 271.5 × 39.3 × 23.4 feet. While she was under Brown Brother’s ownership, the Trafalgar was involved in a collision with George Smith’s City Line barque City of Corinth in March 1888, the incident occurred off the Isle of Wight and the latter ship foundered. On buying the Trafalgar Andrew Weir immediately had her converted to a barque. After loading coal at Cardiff, Trafalgar made a 31 day passage to Rio de Janeiro. On discharge she sailed to New York in ballast and loaded case oil for the Dutch East Indies. But later in the year whilst she was still on her first trip for Andrew Weir, and after discharging the case oil at Batavia, disaster struck! The incident was later reported in the Melbourne Times:

The four masted barque Trafalgar left Batavia in the Dutch East Indies on 29th October 1893 with ‘Java Fever’ on board. The captain died before the ship had sailed and the first mate succeeded to the command signing on another man to take his own place, with one of the sailors acting as second mate. On their way across the Indian Ocean the new master, Captain Richard Roberts, and his new first mate both succumbed to the Java Fever plague and died. The navigation of the ship then fell upon the shoulders of the acting third mate William Shotton, an 18 year old lad who was still serving his apprenticeship. The second mate who had been promoted from the crew proved to be worse than useless and William Shotton sent him back to the foc’sle. Imagine the task the boy had to face. There was only one other man left on board who could take a trick at the wheel, a sail maker named Kennedy. The rest of the crew for the most part had either died or been stricken with the deadly disease. Yet William Shotton brought the barque safely into Melbourne, riding out a gale and faring up dauntlessly. The Trafalgar arrived at Port Phillip a week before Christmas. The Victorian Government presented Mr Shotton with a gold watch and chain in recognition of his gallantry. Later on he was the recipient of a Lloyds Silver Medal.

Eleven years later on 11th November 1904, the Trafalgar was wrecked 20 miles South of Tamandare, Brazil. She was on passage with a cargo of wheat from Sydney towards Falmouth for orders.

Falklandbank

Built in 1894 by Mackie & Thompson for Andrew Weir, yard number 78, the three masted fully rigged ship Falklandbank registered 1,913 gross tons. Her other dimensions were 265 x 39 x 24 feet. Of the scraps of information found on this ship, one is she collided with the Belgian steamer Switzerland, Captain Doxrud, at Antwerp on 5th July 1905. As a result eight plates on the steamers hull were stove in and left a 30 inch hole below the waterline on the starboard side. Most fortunately the Switzerland’s cargo had been discharged. A claim for £4,000 was made against the Falklandbank and the tug Flying Serpent, the towing line which parted was the cause of the accident. She met her end in the winter of 1907-1908.

Transcript from the Liverpool Mercury, 9th May 1908

Grave anxiety is being manifested in Liverpool for the safety of the steel ship Falklandbank, which is overdue on her voyage from Liverpool and Port Talbot towards Caleta Beuno. She arrived in Liverpool on 2nd October 1907 from Caleta Beuno to load for the West Coast of South America (WCSA) through the agents William Lowden & Co., 17 Water Street. The crew signed on at the Central Shipping Office in Canning Place with a large number of her men coming from Liverpool. Prior to leaving the Mersey she was in Glover’s Graving Dock and should have been in good sailing condition.

She left Liverpool on 24th October 1907 and arrived at the Welsh loading port two days later where she remained until 9th November when she sailed for Valparaiso. She was in contact two days after leaving port in 49° North and 8° West, and then again in 31° South 46° West by the Italian ship Checco which arrived in Montevideo on 27th December.

The American ship Kenilworth had been caught in a heavy gale, otherwise known as a Pampero on 30th December off the River Plate. She was thrown onto her beam ends which resulted in her subsequent loss. It is feared that the Falklandbank was possibly overtaken by the same gale, as she would have been in the same position at the time. Captain J. A. Robbins her master has been 35 years in active service and for the past ten years had been in the employ of Andrew Weir & Co. of Glasgow. At about the same time that the Pampero hit the River Plate region, a terrific storm was raging off Cape Horn which resulted in the loss of six ships. It is a possibility that the Faklandbank was there at the time. The Falklandbank has to date been 180 days out of port. The Liverpool ship Barcore left Barry nine days after the Falklandbank and arrived at Caleta Colosa on 20th March 1908 after a passage of 123 days.

The continued absence of the Falklandbank is causing great anxiety in shipping circles and it is feared she has been lost with her crew of 30 men. Although several of the Liverpool crew deserted at Port Talbot, it is known that many of those who sailed in her come from the Mersey port.

The Sailing Ships Of Andrew Weir Shipping And Trading Co. Ltd.

| Name | Built | Builders | In Service | Tons | Fate |

| Willowbank | 1861 | Wigham, Richardson | 1885-1895 | 882 | 1895 – sunk in collision off Portland |

| Anne Main | 1867 | Alexander Stephen | 1886-1896 | 499 | 1896 – wrecked at Goto Island |

| Thornliebank (1) | 1886 | Russell & Co. | 1886-1891 | 1,405 | 1891 – fire at Perth |

| Francis Thorpe | 1868 | Richardson, Duck & Co. | 1888-1890 | 1,257 | 1890 – wrecked at Salinas Cruz |

| Abeona | 1867 | Alexander Stephen | 1888-1900 | 1,004 | 1900 – wrecked at Cape Recife |

| Pomona | 1867 | Steele & Co. | 1889-1902 | 1,253 | 1902 – abandoned off The Azores |

| Hawthornbank | 1889 | Russell & Co. | 1889-1910 | 1,369 | 1917 – torpedoed off Scotland |

| Hazelbank | 1889 | Connell & Co. | 1889-1890 | 1,660 | 1890 – wrecked on Goodwin Sands |

| Elmbank | 1890 | Russell & Co. | 1890-1894 | 2,288 | 1894 – wrecked on Isle of Arran |

| Sardhana | 1885 | Russell & Co. | 1890-1911 | 1,146 | 1911 – wrecked off Uruguay |

| Comliebank | 1890 | Russell & Co. | 1890-1913 | 2,283 | 1913 – abandoned off Bermuda |

| Dunbritton | 1875 | McMillan & Son | 1891-1906 | 1,536 | 1906 – sank in the North Sea |

| River Falloch | 1884 | Russell & Co. | 1891-1909 | 1,637 | 1922 – broken up |

| Trongate | 1878 | Dobie & Co. | 1891-1917 | 987 | 1925 – broken up |

| Thistlebank | 1891 | Russell & Co. | 1891-1914 | 2,430 | 1914 – torpedoed off Ireland |

| Gowanbank | 1891 | Russell & Co. | 1891-1896 | 2,288 | 1896 – abandoned off Cape Horn |

| Ashbank | 1891 | Russell & Co. | 1891-1892 | 2,292 | 1892 – disappeared |

| Beechbank | 1892 | Russell & Co. | 1892-1913 | 2,288 | 1924 – broken up |

| Fernbank | 1892 | McMillan & Son | 1892-1902 | 1,429 | 1902 – wrecked off Mozambique |

| Oakbank | 1892 | McMillan & Son | 1892-1900 | 1,429 | 1900 – wrecked on Serrano Island |

| Cedarbank | 1892 | Mackie & Thompson | 1892-1913 | 2,825 | 1917 – disppeared |

| Olivebank | 1892 | Mackie & Thompson | 1892-1913 | 2,824 | 1939 – mined off Jutland |

| Trafalgar | 1877 | Connell & Co. | 1893-1904 | 1,768 | 1904 – wrecked near Recife |

| Mennock | 1876 | London & Glasgow Eng. | 1893-1916 | 822 | 1923 – wrecked at Punta Lirqen |

| Levernbank | 1893 | Russell & Co. | 1893-1909 | 2,400 | 1909 – abandoned off Scilly Isles |

| Laurelbank | 1893 | Russell & Co. | 1893-1898 | 2,397 | 1898 – disappeared |

| Forthbank | 1877 | Dobie & Co. | 1894-1909 | 1,422 | 1911 – wrecked at Chinchas, Peru |

| Castlebank | 1894 | Russell & Co. | 1894-1896 | 1,656 | 1896 – disappeared |

| Heathbank | 1894 | Russell & Co. | 1894-1900 | 1,661 | 1900 – disappeared |

| Falklandbank | 1894 | Mackie & Thompson | 1894-1907 | 1,913 | 1907 – disappeared |

| Loch Eck | 1874 | Connell & Co. | 1894-1895 | 1,701 | 1906 – dismasted and hulked |

| Springbank | 1894 | Russell & Co. | 1894-1913 | 2,398 | 1920 – wrecked off Stavanger |

| Isle OF Arran | 1892 | Russell & Co. | 1895-1915 | 1,918 | 1915 – sunk by U-boat off Kinsale |

| Collessie | 1891 | Russell & Co. | 1895-1901 | 1,465 | 1901 – wrecked off Chile |

| Clydebank | 1877 | Birrell, Stenhouse & Co. | 1895-1901 | 893 | 1913 – damged and hulked |

| David Morgan | 1891 | Wm. Hamilton & Co. | 1896-1898 | 1,566 | 1898 – disappeared |

| Perseverance | 1896 | McMillan & Son | 1896-1900 | 1,900 | 1900 – disappeared |

| Thornliebank (2) | 1896 | Russell & Co. | 1896-1913 | 2,105 | 1913 – wrecked off Scilly Isles |

| Allegiance | 1876 | Potter & Co. | 1897-1900 | 1,236 | 1900 – abandoned on fire |

| Loch Ranza | 1875 | Connell & Co. | 1897-1901 | 1,129 | 1925 – broken up |

| Gifford | 1892 | Scott & Co. | 1898-1903 | 2,245 | 1903 – wrecked near San Francisco |

| Gantock Rock | 1879 | McMillan & Son | 1900-1909 | 1,611 | 1924 – broken up |

| Glenbreck | 1890 | Duncan & Co. | 1900-1901 | 1,900 | 1901 – disappeared |

| Ellisland | 1884 | Duncan & Co. | 1908-1910 | 2,426 | 1910 – disappeared |

| Philadelphia | 1892 | C. Tecklenborg | 1912-1915 | 1,805 | 1917 – torpedoed off Ireland |

The company also bought the sailing ships Poseidon (built 1881) in 1908, and Marion Frazer (built 1892) in 1911 and converted them into storage hulks.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item