“I feel instinctively that Providence has created France for complete success or exemplary misfortunes”.

General de Gaulle’s perceptive summing up of the national psyche could equally apply to the country’s principal shipping line. Of all the Atlantic players, none conjured the full spectrum of experiences and emotions, from elation to despair, as dramatically as the French Line.

The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique , abbreviated to CGT or ‘Transat’ in France and universally known as the French Line, emerged as a government funded successor to the Compagnie Générale Maritime, a fledgling shipping company established in 1855, by Emile and Isaac Péreire. Like their contemporary, Samuel Cunard, these sons of Portuguese emigrants were already prominent businessmen, for whom the steamship represented a fresh commercial opportunity.

Using their extensive contacts and influence in banking (they had established much of their wealth and reputation as financiers) and the imperial court, in 1861 the Périere brothers acquired a certain Louis Victor Marziou’s concession to operate a regular steamship service across the Atlantic to the Americas, together with an annual government subsidy of 9.3 million francs. In return they contracted to carry mail, with a guaranteed minimum of 26 roundtrip voyages on the principal service to New York. If the practical purpose was to carry the post, Emperor Napoleon III’s decree at the company’s inception already hinted at a broader commission, “to uphold and maintain the prestige of France on the Atlantic”.

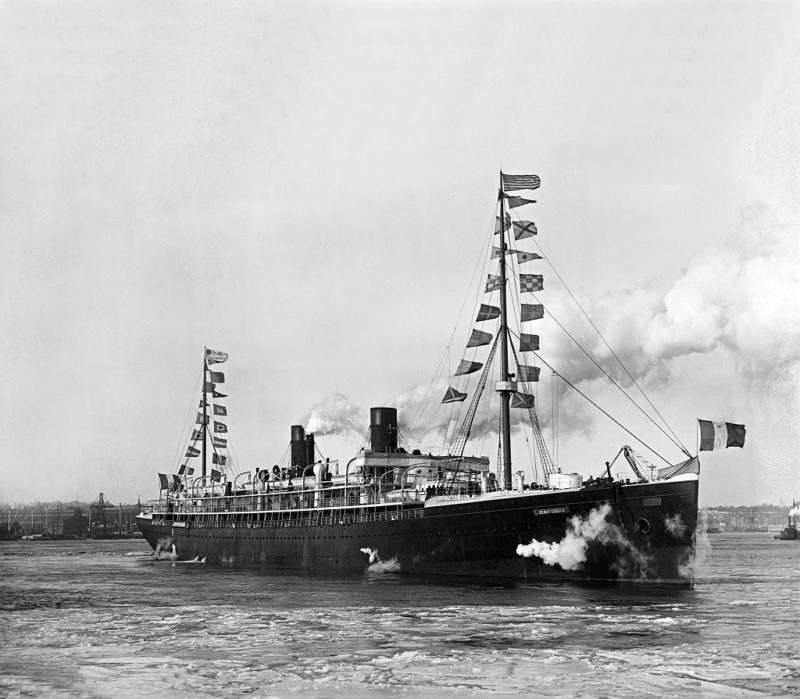

On 16th June 1864 the company’s first ship, Washington, departed Le Havre inaugurating the famous service to New York. Over the ensuing century the utilitarian named home port (literally ‘the harbour’ in English) steadily grew in unison with the company steamers, however its constraints significantly prejudiced CGT’s development.

Washington and her sisters, Lafayette and Europe were built by Scott’s of Greenock. Commercially this made eminent sense, the Clyde was then the fulcrum of the nascent steamship building industry and those French yards that tendered for the contracts were not only more expensive, but also unable to provide the necessary infrastructure, technology or expertise to rival that concentrated in Scotland. Regardless, the political imperative was to build the ships in France, so the Périere’s and the Parisian government came up with a radical solution.

After researching suitable sites, CGT purchased sixty two acres of largely barren wasteland on the northern shoreline of the Loire estuary, encompassing the fishing village of Penhöet and close to the industrial city of St. Nazaire. Local shipwrights were trained by a delegation of John Scott’s workforce (including the great man himself), as Emile Périere’s vision of ‘a mighty and sophisticated workshop’ emerged from the surrounding marshland. Chantiers et Ateliers de Penhoët subsequently became the birthplace of almost all the famed French Line liners and ultimately the very last liner of them all, Queen Mary 2.

At sea and in the boardroom Transat was beset by misfortune in that first decade of trading. There were groundings and collisions but also Emile and Isaac Périere were forced into bankruptcy by the financial crisis of 1868 and consequently relinquished their positions on the board. Two years later, the whole nation was left reeling by defeat in the Franco-Prussian war, the bloody suppression of the ensuing Paris Commune and the unpredictable origins of the Third Republic. Just as the company was re-establishing itself, Ville du Havre, which had originally been completed as Napoleon III, collided with the sailing ship Loch Earn and sank with the loss of 226 souls in November 1873.

In the face of such challenges and despite their close associations with the now discredited Second Republic, CGT’s board once more turned to the elderly Périere brothers for inspiration. Emile died in 1875, but Isaac and in particular his son Eugène, joined the board and would prove instrumental in transforming Transat’s fortunes over the next quarter of a century.

Subscribe today to read the full article!

Simply click below to subscribe and not only read the full article instantly, but gain unparalleled access to the specialist magazine for shipping enthusiasts.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item