By Ken Williams

![]() During the early 1970s, Britain was in the grip of a downward economic spiral with never-ending strikes and rising inflation. To many seafarers, like myself,

During the early 1970s, Britain was in the grip of a downward economic spiral with never-ending strikes and rising inflation. To many seafarers, like myself,  visiting other English-speaking countries appeared to offer more opportunities for advancement and in most cases a better life in the sun. In January 1974, I took some unpaid leave in order to explore southern Africa as a potential place to live and I eventually ended up in Salisbury, Rhodesia. In April of that year, Portugal announced a withdrawal from her overseas territories in Africa, following a military coup in Lisbon. This sent shock waves throughout Rhodesia, as the country now faced an additional counter-insurgency campaign against groups of armed guerrillas along its long border with Mozambique. With no political solution in sight, I decided to return to the UK and complete the second engineer’s Certificate of Competency course. A single air ticket to London from southern Africa was prohibitively expensive so I thought a cheaper alternative would be to work my passage home from a South African port. For this I needed my discharge book and British seaman’s ID card, which my father duly sent me.

visiting other English-speaking countries appeared to offer more opportunities for advancement and in most cases a better life in the sun. In January 1974, I took some unpaid leave in order to explore southern Africa as a potential place to live and I eventually ended up in Salisbury, Rhodesia. In April of that year, Portugal announced a withdrawal from her overseas territories in Africa, following a military coup in Lisbon. This sent shock waves throughout Rhodesia, as the country now faced an additional counter-insurgency campaign against groups of armed guerrillas along its long border with Mozambique. With no political solution in sight, I decided to return to the UK and complete the second engineer’s Certificate of Competency course. A single air ticket to London from southern Africa was prohibitively expensive so I thought a cheaper alternative would be to work my passage home from a South African port. For this I needed my discharge book and British seaman’s ID card, which my father duly sent me.

Entry into South Africa could be difficult for those with insufficient funding to support themselves. I was told that it might be less hassle to enter through South West Africa (now Namibia), a journey from Salisbury to Cape Town of over 2,000 miles, via the Kalahari Desert. I left Salisbury with a rucksack, a sleeping bag and around £30 in my pocket. Lifts across Rhodesia to the border at Botswana were relatively easy to come by, in contrast to the infrequent chances of transport across the 600 miles of the Kalahari Desert that lay ahead of me. At one small native village in the desert, I was stuck for three days before I could hitch a ride squeezed into the back of a pick-up truck which I had to share with a goat.

Eventually, I arrived at the small South West African border post from Botswana where the South African border guard asked me what my business was in South Africa. I said I was on leave in Rhodesia and was joining a ship in Cape Town. After examining my seaman’s papers, he granted me a month’s stay in South Africa.

The road leading to Cape Town did not have much long-distance traffic, except for Portuguese settlers fleeing from Angola and they normally did not have enough room for me amongst their worldly possessions. However, once I crossed into the Cape Province, lifts became easier to get and I soon made it to the Seaman’s Mission in Cape Town. The Mission padre could only offer me a shared room at just over a rand (£1=1.6 rand) per night. He asked me with some trepidation if I was willing to share the room with a coloured man. My roommate turned out to be a very pleasant fisherman who was waiting for his next boat. The padre kept me informed every day of the shipping movements in the port. The only vacancies available for an engineer were on a Greek-flagged vessel going to the Mediterranean and on another ship bound for Indonesia.

I tried the local offices of British shipping companies trading with South Africa. The Harrison Line Agency were not aware of any vacancies in the near future. In the British & Commonwealth Group office, one of the superintendents said to me that the Company would be reducing its fleet, leaving little scope for further recruitment.

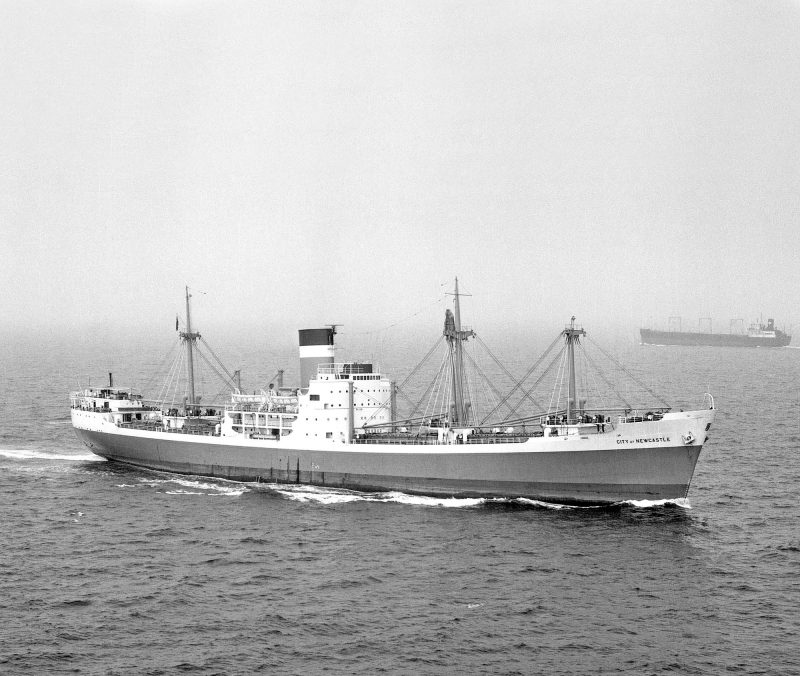

My final call was the Ellerman Lines office, a company I had sailed with three years earlier. There I met Captain Tony Wetherly, who was sympathetic when he heard my predicament, and offered to send a telex to London asking about any possible openings for engineers. With less than two weeks left on my South African permit. I proceeded to call at the Ellerman office every morning to find out if there had been any response. At last there was a short message: “What has Williams been doing since he left the Company in 1971?” Tony and I put together a brief employment history and sent it off by telex. There followed further days of waiting before finally, with only a few days left on my permit, a message came back from London: “Williams to join City of Newcastle as 4th Engineer at Mombasa on 1st July 1974.”

Ellerman City Line operated an altruistic personnel policy, whereby if any of the sea-going staff suffered any personal or emotional problems the Company would, in most cases, repatriate them home from anywhere in the world. I was later to find out that two of the junior engineers had been flown home for personal reasons, hence the opening for a fourth engineer.

Sign-up today to read the full article!

Simply click below to sign-up and read the full article, as well as many others, instantly!

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item